Anders Erik Stenstedt was born in Sweden November 25, 1958. His father (Erik Anders Stenstedt 1924-2007), came from Lappland in Northern Sweden, emigrated to the US in 1951, went back to Sweden, moved to CA, B, Tehran and back to CA. He moved to Sweden 1954-66 with his American wife (Dorothy Harriet Smith), where Anders and his three siblings were born. In 1966, the family moved away from Sweden for the final time. Anders returned in 1983, and spent the summer in Lappland, visiting relatives and family friends, to piece together this history and heritage story of his wanderings and his wandering family.

Anders Erik Stenstedt

andersten1@yahoo.com

Vi flyttade till Amerika 1966. Jag var nästan 8 (åtta) år gammal. När vi bodde i Sverige åkte vi till Kalifornien varje sommar. På den tiden, var det mäst båt transport mellan Europa och Amerika. Jag kommer ihåg båt resan den sommar 1966, när vi flyttade, resan mellan Köpenhamn och New York på båten som heter “Gripsholm.”

MS Gripsholm https://g.co/kgs/rtrbr2

Min mamma, Dorothy Harriett Stenstedt (b. 1930 Dorothy (Dot) Smith) som vanligt, blev skjuk just på början, kräkste up middagn, och hon var sjuk hela resan. Vi hade med oss Fru Karlson som barnvakt och hon hjälpte till mycket.

När vi bodde i Amerika, så skulle vi bli Amerikansk förstås. Sådant, glömmde vi Svenska språk nästan helt och hållit. Vi bodde (både är inte rätt ord) den tiden i Lafayette Kalifornia. Där, min pappa, Erik (1924-2007), även om han var på någon resa det flästa tider, han kunde spela riktig Fotbol (Soccer) och han var riktig duktig på skidåkning.

Även om Jag glömmde min Svenska i Kalifornien, jag tog någa av min Svensk historia. Skidåkning tykte jag var bästa som fanns.

När jag var elva (11) år, då reste jag till Sverige med min pappa (Erik) en sommar. Pappa, han lämnade mig (mej) Blidö (Ö på Stockholm skärgård) med Stenstedt familjen (kusiner med kära Karin) och där skulle jag lära om min Svensk språk. Jag var i Sverige igen sommaren 1974 när min syster, min bror och jag blev konfirmerade i Svenska Kyrkan. Då bodde vi på Mälaren sjön, i en liten små by som heter “Hjo” (se Vättern Sjö i Västdergötoland).

Igen, har jag många historier från den sommar och ifrän min bakgrund men ingen, eller inte någ, tid at berätta. Tack.

Jag var i Sverige igen flera gånger därefter. En gång, i 1983 äfter jag var med på filmen “Hot Dog” gjorde jag släkt forskning om min far och hans familj i Stensele trakten av Norrland, på Ume älven. Det var så kul; där fick jag läsa om livet på gamla tider, där uppe i Norrlands kylet, prata med dom äldre folk, och jag skrev up mycket här som följande.

Det här går ganska bra för mig att skriva upp minnelse. Tack för att du läser.

This book was edited by Gordon William Russell (gordonrussell907@gmail.com)

Introduction – the train back to Lappland

Along with fifty other inter-railers at midnight in Ånge, halfway through Sweden, hoping for a space to rest, I board the luxurious Swedish night train for Norrland. This mid-August, summer- rush-specimen is packed like an Italian train, it yields no space even on the floor. So, I join my pack on a luggage rack, the shelf under the roof across from the bathroom. Here, I find enough place to curl up and rest for a few hours. The conductor complains because he hears my Swedish tongue and wonders how I travel on Inter-Rail in Sweden. I show him my U.S. passport, and he wishes me a good journey.

The seats are full of well organized, vacationing old Swedes, and boys on their way to military stations in Umeå and Boden, they all know to reserve a sitting place. The young Americans tried to book a place, but the small country station couldn’t exchange their pre-bought reservations. They complain loudly when ousted by the conductor. The German groups lie happily on the floor stretching themselves fully, which makes the lavatory inaccessible and my jumping down from my perch a serious risk to them below. The Germans talk louder than the Americans, but with these two groups dominating, Swedish sounds like the foreign language. I content myself with a neck cramp and wait for the four AM stop in Vännäs.

Finally, I stand by the door watching the barren landscape pass. Shivering, I wonder how quickly a town can appear in this wilderness. The train stops and the full daylight disguises the early hour. The boys moving to Umeå for the year of “lumpen” board the rail-bus to the coast. This leaves no more travelers in the station except myself. So, I find a bench in the waiting room and sleep comfortably stretched out until six AM when the train to Storuman attracts a dozen passengers. More forest and marshes along the Ume River, and Lycksele pops up like a piece of the real world. It seems to cling to the river, road, and rails for communication south. And then, I remember the TV and telephone, and Lycksele might live next door to Los Angeles, with a gold mine.

It rains lightly in Stensele, no warmth in the air, and I wonder how long I can last against this climate. A rainy cold weekend in Stockholm after too much train travel and parties in Paris and Bruxelles and my body feels clogged and ready to collapse from cold and fatigue. The schedule says to start with Irene, my Farmor Lilly’s sister. At eighty-six she still has energy to remind me of Lilly the last time I visited, 1976. I continue to the old-folk’s home to visit a cousin of my father’s, Alfred Johanson. He’s getting over a stroke and his wife Elsie treats me like family.

They fix me up with coffee and sandwiches, and a bicycle. Johan Anderson (another relative) across the street has the key to Boxan. For the first week, I rest and simply enjoy the peace of life at Boxan, the old log cabin alongside the Ume River. Reading hard into the history of the world and contemplating my travels, I start to question the potential richness of my family’s history among the trees, rocks, and moss along this river.

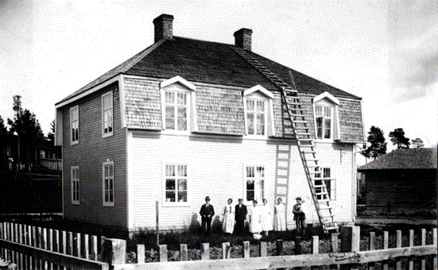

Figure 1: the Boxan cabin, built by Fritz (not 1922)

My Farfar Fritz built the little log cabin “Boxan” with his father, Frans Gustaf Johanson, in 1905. In 1936, they say Fritz moved the old hay storage house or “fäbod” (maybe not, because a fäbod was a cabin for cows, not people) to this jetty or “udde.” For years, he extends and finishes inside and outside

this family summer shelter, only three kilometers from their home in Stensele. Actually, the story goes that one autumn berry picking expedition leaves Lilly and two small children stuck under a tree while thunder and lightning accompany a heavy rain; Fritz forages out to rescue them on his bicycle and decides to begin moving the fäbod next summer. But the big house in Stensele, which Fritz built in 1922, also carries lots of history, and so does his family’s house in Skarvsjöby; and Lilly’s home in Lönnberg proves a wealth for my growing excitement.

I begin with Irene and ask all the questions that come easily to mind in connection with the old family. Continuing with all the relatives that live within range of my borrowed bicycle, I find Henning and Hilda the only remaining family in Lönnberg, waiting for no one to take over the ancient farm. In Skarven, Rolf Robertson lives in a hundred-year-old house and, as he says, the storage shed provided a castle to the early family for most of the 1800s. Knut Fällstam, a younger brother to Fritz, provides stories for me from that side like Irene knows from Lilly’s side. Tora and Kalle Lindahl, also from Skarvsjöby, give me a place to shower and have a good warm meal; since, without electricity and only the coldest of river water, I try to accommodate with cold wash and fire heated food and coffee at Boxan. And I dig deeper into the history, as the story unfolds.

II. Lappland’s History – early settlers

From Lönnberg and Skarvsjöby to Stensele, Stockholm and Göteborg (Gothenburg in English), to San Francisco, Long Beach, Minnesota or Edmonton in Alberta, Canada, the family from the Stensele kommun (socken) spreads to the new world. Those who attack the modern world in Sweden wind up in Stockholm or Gothenburg. But the young today (1983) continue this Lappland exodus. Unemployment, of course, and lack of interest, to compare with the world of books, magazines, and television, make Stensele nothing more than a relic from the past, and nature’s spectacle for the tourist. To accept this old and slow way of life might mean retiring from serious competition. And the modern world doesn’t fit quite right in this wilderness, although, a modern-day care center for the local children, lumber equipment dominating the forest, and cars everywhere, reveal the high standards, evenly spread throughout this region today. But, modern Stensele depresses me, and I grow fascinated with the old lifestyle. The culture, which the stories carry through time, extinguish so easily with technology and cities, but left in their beautiful natural setting. Lappland’s history grows like the wildflower and the forest itself.

The attitude of the old people here shows both pessimism and hope. Irene enjoys all my talk of the new world, though she never escapes her past. She loves to tell me stories of her childhood and brother Arvid who never returned from America. Farfar’s brother Knut sees more of the negative and complains that youth have no concept of real work, no feeling for nature. And I agree that the physical burden of labor can never return to the condition of fifty or a hundred years ago; while the machines roll over the forest, and a man’s duties shift to controlling this amazing power. The contact with nature, however, returns from a modern perspective. As in my life, the next fifty years either frees us from these earthly bonds or moves us backwards and reattaches us to the ways of old, which might be one view. But, before contemplating any future, I feel a need to understand the past; and the lives of these oldsters and their parent’s parent’s stories, speak truer to life than facts and history in my humble opinion (imho).

I return to Sweden less and less as a tourist. My family moved from here to California in 1966. Then, I felt more Swedish than American, now the reverse. For fifteen years, my mother’s family in Texas and California dominated our ancestral understanding. My father, of course, naturalized his citizenship to the United States, and the impetus to forget and ignore the land of our birth grows strong. Inevitably, however, the distant contact breaks into our complacent, new world upbringing and my family maintains excellent opportunity for travel. So, each time I rekindle the family contacts with Sweden, the sense of belonging to these inherited roots carries me to a greater love for the land and its people, more than ever I feel for the capitalist, young, uncultured environment in California, where the sun tries to shine all the time. Sweden grows in me, more like my own, my home, only to conflict with reality, for California and family will always call me back. A longing struggle indeed, and thus, today I write.

The contrast seems less grave than in history because our modern world takes such pride in the speed of distant communications, and flights get cheaper every year. This family Stenstedt, and our blend of old and new world, represents to me a significant piece of international society.

And this story means to join two radically different cultures. Like town and country, science and nature. One might argue that nation states might rule by legal terms, while our global humanity governs our thoughts, linking us to ground Earth, and protective economic, and ultimately capitalist, policies prevail. But for me, as culture and science race to discover the modern and future ideas, this story accepts the findings of the ancient way of life. Competition matches individual against individual, institutions against ideals; but, in these older times, life revolved more naturally around the earth, with God, family and community cooperation. Life today might hold a less physical concept of work, but the family structure holds the same precepts as in the old culture, which gives me the ultimate souvenir to take back with me.

From my travels and sejour in Sweden, I seek to find a sense of roots, a feeling of family. And this paper simply records that which I discovered from interviews, as much scholastic study that my undisciplined and unrefined Swedish permits, and my impressions, my imaginings of a world left behind. I can’t help but think that something was lost in the translations and over time, but still . . .

If I could describe Stensele very simply, along with this whole Swedish background, I use four words: weather, work, family, and religion. The climate rules the environment, especially in Northern Sweden and specifically Lappland. The harsh nature of winter dominates all aspects of life in the region for its extended nine-month season. Fall and winter acts as minor prelude and postscript, while summer leaves only a short respite. It is during these three moths of summer that the farmers prepare to surmount the major hurdle of surviving the coming cold in Lappland. This leaves such a short time that summer’s work here carries the press of the

weather’s rush. Hard manual labor is required here, with only a few tools to relieve the burden of farming this soggy arctic soil, in a real hurry from the time of sufficient thaw until the freezing air sinks through the ground again. Persistent, disciplined, progressive farming must combine with good luck (God’s blessing) to survive devastating blows of nature, like the winter of 1877, so goes the story.

Family, of course, nourishes the work ethic, creating a bonded unit. They work together and for each other. The family extends to the community, though the channels of communication remain minimal. The unit self-perpetuates and adds to the efficiency of the farm itself.

Essential as the work is to survival, work might take precedence to family in order to assure the basic necessary comforts involved with establishing a home. Ultimately and overall, then,

religion pleads to the unknown, the ruler of fate and the Earth. Man’s fragile nature seeks a force, like a supernatural protection. This mutual belief among Swedes in the expanding territories of Lappland, arguably carries over into the heathen “Samer” culture, which lives long before any attempt to colonize in this wilderness. At first, the Lapps resented the emigrants and their strange God, and even today, the Samers cling to their disappearing culture. Among the colonizers, however, the mutual effort to combat the winter, and maintain a church community, maximizes their power. This sense of spiritual and physical strength exists in Lappland at the base of their simple and strenuous, farming spirits.

It becomes even harder to find this basic lifestyle in direct harmony with the flow of nature on this civilized Earth today, I would argue. Only the most remote families and communities retain a routine with such hard work and primitive means of survival, like the Lapps. In our modern world, technology, and machinery, so often replace manual labor, the hard work ethic disappears, and religion follows suit. The need for faith in the powers of the church dies along with any definite use of the extended family. The progressively independent role of the individual in a world working on market economics and growth of capital goods replaces the farming family here and there in the world over. Intellectual pursuits, such as this treatise, may provide comfort, as culture and modern material pleasures substitute for the simplicity of homelife. But families still exist the world over and employ the same principles of work to live. This story shows use of the extended family, now as far apart as the world affords. And maybe, success in this world depends even more on the family, just like the old work ethic, as hard physical labor, and contact with life’s blood, like personal production responsibility, might trail off in the wake of machines. Like technology manipulated to affordable levels, integrating the most primitive homes to relieve the burdens of living, exist but they also sever the soul from the spirit. This old system in Lappland makes passable the road for those who climb out to modern status early. Nevertheless, the rest, left behind, receive their dose of the modern world wherever they stay, seemingly to alienate nature. Those who leave Stensele find the world first, the rest wait patiently, and the world comes to Stensele. To my thinking, this new culture doesn’t seem to fit quite right in old Lappland.

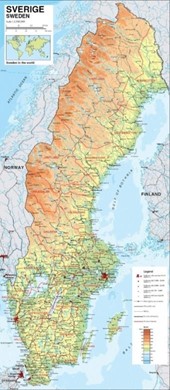

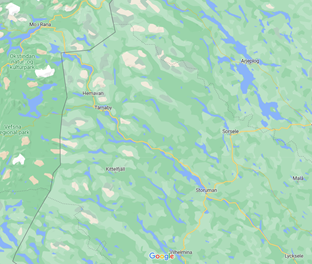

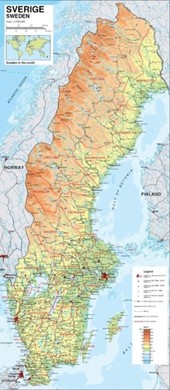

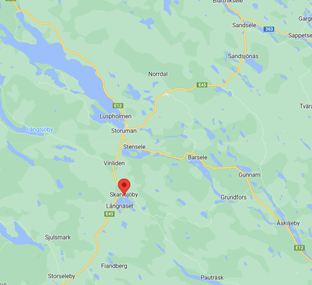

Figure 2: Lappland

From pre-history to stone age and iron age, we find the last of the glacial ice finally melted away from these pre-Cambrian rocks, to form more or less the Swedish coastline. This stretch along the Bothnian Sea runs around from the North Sea and up to 66 degrees latitude and across east and back down the coast of Finland. In the west, Sweden and Norway separate with a mountain range, which comprises most of Norway. The eastern slope of these mountain “fjälls” creates the northern forests of Sweden, three to four times as wide as the Norwegian mountains.

Norway and Finland meet at the northern border of Lappland in Sweden. Overall, Sweden takes the most fertile land and fresh water natural irrigation system of the north (Lappland). This creates the opportunity to expand civilization inland for farming in this northern region in early days. As we see, this desolate piece of wilderness and sub-polar climate, carries the arctic tundra east, down from the “fjälls” and it defines the North as Lappland. The mass of forest one sees in Lappland today begins expanding only after 1880AD or thereabouts. But archeologists find traces of man as far inland as Lycksele as early as 7000BC. So, at least since the Christian era, we might say, civilized man pursues his life’s activities along the immediate coastline in Lappland.

The Vikings of the North, in ancient times, manifest the marinal lifestyle perfectly. They progress within their limited means, innovating newer styles of fishing, boating and warfare along these marinal lines. The Vikings tested fishing and homesteading all along their immediate coasts, spreading their advanced, aggressive naval culture throughout Europe and Asia in the Middle Ages. This expansion proves a massive development for the scale of human communications, like Islam for the North, seven to nine hundred years after Christ (AD).

Figure 3: United Sweden/Finland

Figure 4: Ales Stenar

The Swedish Vikings spread around the Bothnian, uniting the coastline of Sweden and Finland. They invade and leave settlers down to Smålensk, Russia and farther inland along the Dnepr River down to Kiev, Ukraine. They may even have reached the Black Sea in Siberia, but their settlers stay farther north.

Norwegian Vikes, of course, explore their abundant seacoast protected with the extensive system of fjords. They cross the North Sea to raid the coast of England and Scotland. They leave many settlers on Iceland, a desolate island promising no more than a harsh climate for survival. These tough Norsk Vikings even see the Americas, they say, after invading Greenland and Newfoundland.

The mere distance of these marinal expansions leave the settlers thin of populous power, I guess. And the brunt of Viking cultural contribution remains their successful raids and barborous plundering. “Skål” they might shout raising the conquered and severed skull, filled with hard alcohol, and they salute their victory, so goes the tale. Then, they move on to the next enemy.

The Danish variety of these Viking warriors causes a tremendous fear throughout medieval Europe. They move their warring ships through France and Germany, say the history books, down to the Mediterranean, where they meet up with the armies of Arabia and Islam. Overall, generalizations find that Norsemen mean to colonize, Swedes to trade busily, while the Danes gain fame for their ruthless plunder of sanctified Catholic shrines, where treasure and food lie so conveniently centralized, and they plundered in Asia. But the Vikings spread themselves thinly, and they succumb to the domination of the Christian church, ending the Viking culture with the end of the Middle Ages. Europe then discovers the newest technology in marine travel, and warfare, of course, especially. Spain and England come to dominate. Scandinavia, on the other hand, settles down to the Royal rule of Kings willing to submit to the authority of the Holy Roman Empire, which lasts until the Reformation and the age of Enlightenment. So, wars continually change the look of the entire continent, and Scandinavia succumbs to the power of treaties. Kingdoms grow to command ever larger states, and history balances out the borders in the North until they resemble approximately the present distinctions.

Three Scandinavian countries exist in the 17th Century (Sweden, Denmark, and Finland). Sweden still dominates the Bothnian coast and Finland remains a mix of Slavic and Swede. But for our purposes, the expansion of civilization remains close to the water and south of the Arctic. More than twenty kilometers inland to Lappland, the people of this age might consider the border with wilderness. Not until overcrowding forces expansion, do the people of the North begin to explore the open spaces farther north and inland toward the “fjälls” in Lappland.

During the late sixteenth century, Germany aligns with Holland, Scotland, parts of France, England, and the entirety of Scandinavia to join the Reformation revolutionizing the catholic church and its religious monopoly from Rome. Luther’s Reformation subdues the Swedish church at the time and dominates its policy ever since. Later, the exploration of the new worlds expands the horizons of civilized Europe. Scandinavia, and more specifically, Sweden begins to search and develop its inland areas; moving north, they strike the long-established isolated heathen culture of the “Samers/Lapps.”

The inland movement in Sweden works away from the familiar Bothnian coast, and the explorers use the extensive river network as guide to this wilderness. They follow the rivers to the “fjälls” bordering with Norway. The Norwegians have easier proximity to these mountains, but their culture stays along the “fjords” in the west and connection with fishing the North Sea waters, and trade with the British Isles. Most of the fresh water from these “fjälls” runs to the east and down the Swedish side, which acts as the home grounds for the ancient community of migrating Lapplanders/Samers.

The “Samers” live on fish and reindeer products. Primarily the latter, which demands their continuous mobility. They move their entire families and home from summer feeding in the mountains, then, in winter they follow the reindeer towards the south and the coast. The precise origins of these Lapplanders remains unknown, resting deep in early history. Their race originates relatively far from the Swedish race. Their tongue sounds more Slavic, close to Finnish. Their physical features remind of the Mongolians. Somewhere and sometime, they wandered west from Siberia to find the reindeer, their source of existence in Lappland still today. They live in remote isolation, and so far at least, no need exists to blend their culture or community with society and modern Sweden, except for their obvious historical value and charm for tourists.

One thing the Lapps teach the northern Swedish explorers surrounds the lifestyle necessary to survive the extreme climate offered by this sub-polar environment. The cold and the wilderness presents its burden all over northern Europe, which unites the culture of Siberian slavs, Norwegians and even Irish and Scottish societies with those moving into Swedish Lappland. Simply admiring the artistic luxury and the technology of southern Swedish churches from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, one marks the oneness with continental Europe of this era, similarities of culture and civilization centuries ahead of the North. The weather here in the North radicalizes the people and their society to a more primitive development. As John Ruskin, a nineteenth century architectural critic and writer from England noted, the church from the north helps to design the gothic arch in the south, with its pinnacle reflecting the mountain and rough atmosphere all around. While the southern Romans and their smooth round arches act to reflect their temperate climate and gentle countryside. To me, there remains a rugged excitement in the northern culture, though totally lacking the refinements of Rome.

With each northerly extension of latitude, and distance from the coast, the northern culture distinguishes its development from the south. For the entire land of Sweden, Stockholm dominates for the peoples of the Bothnian sea. The coast shows a history aligned with its capital city, obviously the seat of the Royal throne, and its Church. Stockholm declares itself a city as early as 1200AD. This preempts the peasant influx to city center by many centuries. Lund, outside of Malmö, seems the oldest Swedish city dating back to c:a 1000AD. Uppsala organizes its city-state no later than 1300AD, and for a piece of history farther north, along the Bothnian coast, Gävle finds its place on the map around 1375AD. Moving north to smaller locales: Sundsvall, Härnosand, Umeå, Luleå and Piteå all date their cities to the 1640s. The extended contact with Stockholm and from there to Europe, appears simultaneously in these new cities, where culture seems mostly apparent in the look of the churches. The high sharply pointed steeple of these churches show a union of people and religious culture anywhere north of Copenhagen, Denmark.

History shows how the Church moved inland, along with the Crown’s authority to tax, and to baptize the heathen Lapps. These authoritative predecessors to colonization moved inland, up the Ume River, from Umeå to Lycksele. This expanding movement includes ventures from Gävle to Vilheminna and beyond, also in these early times, similar river exploration shows north of the Ume, along the Skellefteå river, the Piteå älven, and above Luleå to Boden. The Lycksele discovery, in my story, represents one of the main efforts of the state for taxation purposes, and of course, the church’s ideas of salvation for the Lapps. Also, colonization begins in this area for Swedish farmers.

Figure 6: Map with Lycksele and Ume River

In Lycksele, the invading colonizers find an historically established Lapp trading center. From antiquity, it appears, the “Samers” used this “udde” (jetty) along the Ume River for the annual reindeer slaughter and commercial trade ventures. So, the Crown establishes its taxing center in Lycksele, proclaiming all rights to the territory and natural domination of the trading scene. In 1607, they build the first “Samer” Christian church on the commercial jetty of old Lycksele. The tax effort proves as successful as the evangelical. But black marketer Lapps silently boycott the settling Swedes, and some Lapps even swear to fight this invasion of this foreign culture unwilling to accept their ancient Gods. But the nasty winter climate and the addition of hard alcohol in the tradition of the Vikings loosens up the atmosphere of exchange. The rebellious movement fails to attract unifying support. The Christian doctrine promises all its beauty and comfort. The Crown prevails, colonization begins, and “Samers” submit, as they are successfully subdued.

In medieval times, Sweden suffers similar growing pains as the rest of Europe. During and after the renaissance, however, medicine improves, food and nutrition value gains significant respect, and overall, the health standards progress to cause the population growth, leading to unemployed farmers crowding the cities and seeking shelter for subsistence under their Royal rulers.

The economy of this age works on simple handicraft, primarily centering around family labor and the home workshop. This reflects the system of the farm, with the addition of specialization and trade. Collective labor efforts appear with greater frequency with the town economies. In large constructive undertakings like castles, churches, sea-faring ships, and war, certainly the organizers understand how to exploit the power of mass, focused, labor, and capitalizing endeavors. For the normal family, however, the city means a gradual breakdown of the home-handicraft industry. Unquestionably, the case remains the same in Sweden, for centuries, for the majority of families who live off their farming efforts in the country. The individual unit concentrates its efforts to produce its life’s blood. Rural life knows very little of the economic refinements which begin to appear through the city culture.

Gradually, the value of money gains power, as food and housing make cumbersome items of trade. The farther the distance from town, however, the less the people live with money. They live self-sufficiently and independently, ignorant of the dawning revolution of industry throughout Europe. In Sweden, transportation opens the coastline to marine traffic and banking, not to mention engineering and medicine. Inland the rivers run wild, the trails are only manageable by foot.

At this time in early history, a trip from Umeå to Lycksele means a three-to-four-day journey, through wild forest, along a mighty powerful river. Maybe wintertime presents easier traveling opportunities, except for the weather. The invading civilization of colonizers then face a challenging situation to occupy this wilderness of Lappland. In my story, the market in Lycksele opens the first channel, both through taxation, commodities, and religion.

In 1671, the Swedish king Karl XI orders a study of further colonial possibilities along the Ume River above Lycksele. The results show the area capable of supporting some fifty-six families. By 1740, the move to the inland freshwater ways, scattered marshy meadows and growing forest lands, settles families in Luspen, Bastuträsk and Storuman. Soon, the Stensele “socken” area fills with hopeful “nybyggare” settlers.

III. Early Family Settlers in Lappland

Here, finally begins the story of my family, specifically. The traces available through old church books and the crown’s tax records, show four major contributors, among others, in this growing area. One Thomas Erik Norrman from Norrsjö in Skellefteå kommun. Two, Anders Johansson a “bonde” farmer in Mjödvattnet, somewhere between Lycksele and Åsele in the south. Then, on the other side of Lycksele, there’s Jacob Johansson (3) in Degerfors, and Olof Olofsson (4) in Granön.

The first three show the extent of my research, though they must also have their ancestors (see ancestry.com). For the interested, the Härnösand library also has all the church records for Sweden. If I could start there with what I know, I’d look for Anders Johanson from 16651. I checked the old books of Norrman and the Degerfors Johansson, and found the records so faint I don’t believe they can show much from further research. But the last character happens to tie in with Jan Ingemar Stenmark, and the press (Västerbotten Kuriren V-K) traces him back to a Gulle in 1400AD. I didn’t realize our relation when I saw this notice in Tärnaby. And so, for another time, I leave the continuation of back dating.

| 1 The MyHeritage site suggests Anders Johansson was born in 1670, not 1665 |

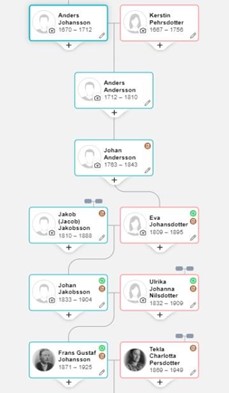

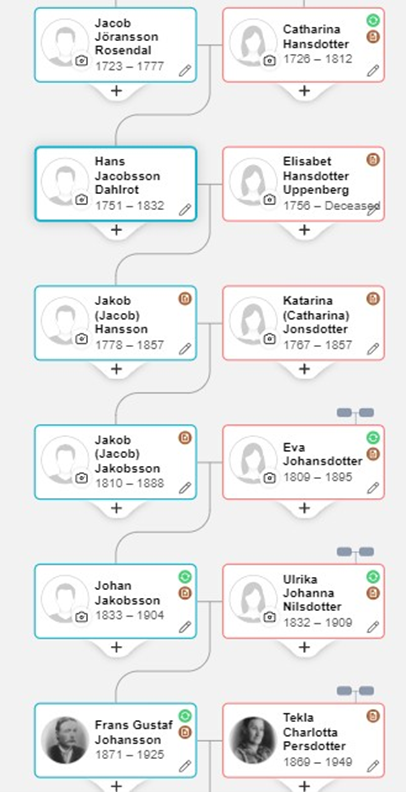

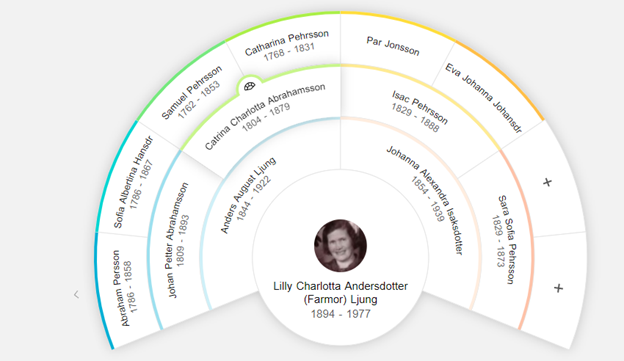

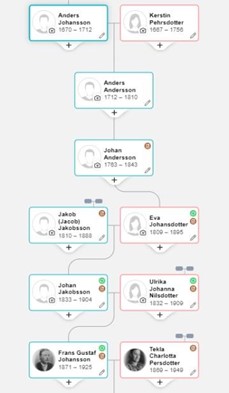

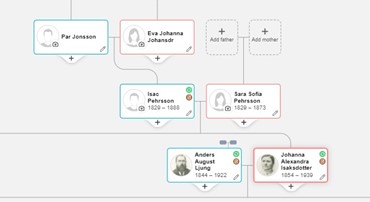

Figure 7: MyHeritage.com detail showing line from Fritz’ father to Anders Johansson

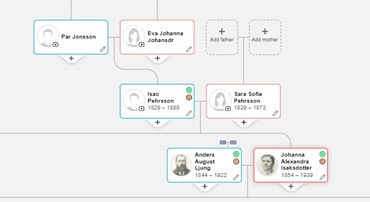

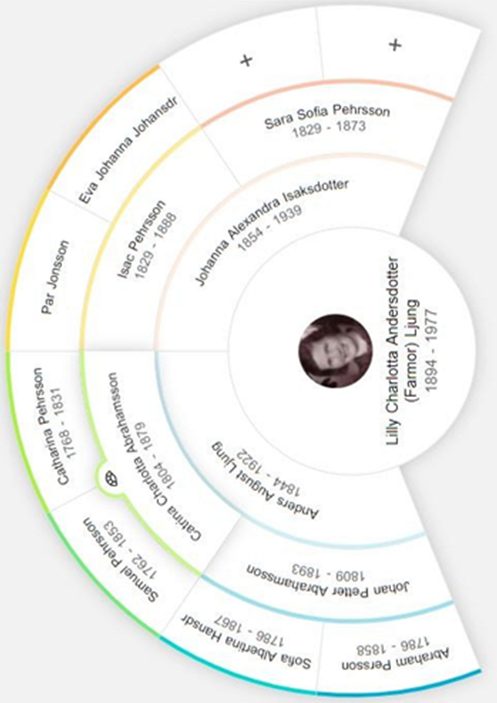

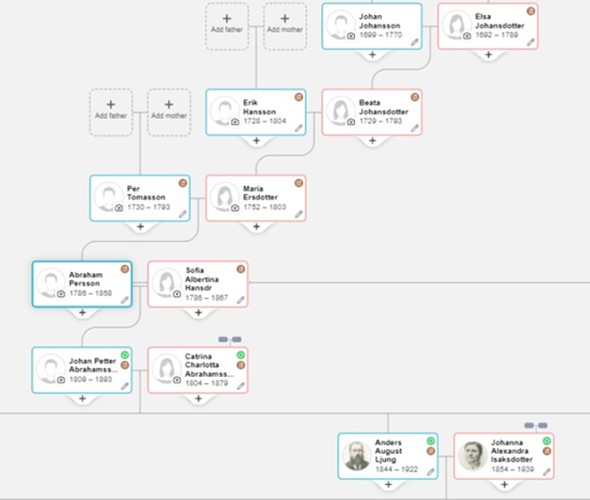

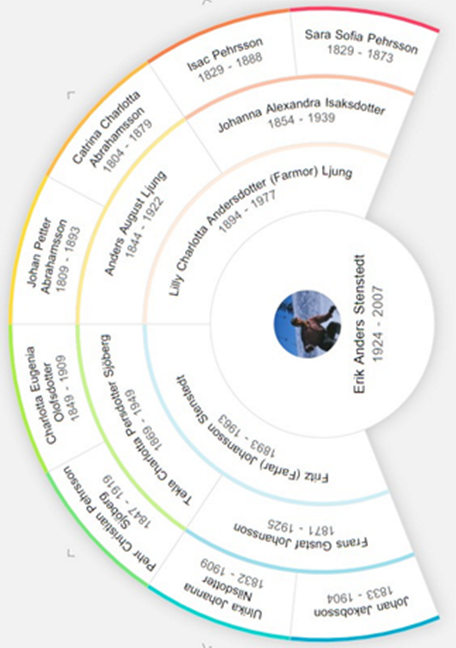

Thomas Erik Norrman’s son, Pehr Thomasson moves to Sandsele, Sorsele. This small village lies on the Sorsele river some sixty kilometers above Stensele. The move takes place around 1750AD. Next in this line comes Abraham Pehrsson who settles a family in Ankarsund, which lies closer to Stensele up the Ume River some forty kilometers. His son, Johan Petter, moves and tries several spots along the river and by the nearby lakes. And his son, Anders August Johansson grows up in Nordanäs very near Umnäs. He learns fishing as a trade and moves north into Norway and up to Narvik as a “lofotenfiskare” fishing the north polar sea during the summer. Quick as a lightning bolt, they say, he earns the nickname “jungen,” meaning a flash in Norwegian, and the name for a purple flowering fern common in the Swedish forest. He meets Johanna Alexandra Isaksdotter, marries her and thus inherits a nice farm in Lönnberg ten kilometers south of Stensele, and birthplace of Lilly Charlotta, my Farmor. The eldest son, August Anders passes this farm on to Henning Ljung who lives there today (1983) and carries the name chosen by the “lofotenfiskare” another Ljung brother to my Farmor Lilly.

Figure 8: Ancestors of Lilly’s father Anders August Ljung

Johanna Isaksdotter traces back to, among others, Anders Johansson, the farmer from Mjödvattnet, Burträsk born around 1665. His son, Anders Andersson outlives one wife and marries another. He sires a total of fourteen children all of whom outlive childhood, a remarkable feat for these times. His youngest son, Johan Anderson (1763-1843) moves to Långvattnet and starts a huge family of his own, which spreads throughout the Stensele community. All ten of his children start a family in this area. Three of them lead directly to my family. Son, Pehr Johansson (born 1800) marries Eva Stenvall (born 1804) from Stensele. They have a son named Isac Pehrson (1829-1888). He marries his first cousin Sara Sofia Isaksdotter (1829-1873) whose mother Anna Christina Johansdotter (b. 1804) comes from the same Johan Andersson and Maria Mattsdotter in Långvattnet as her brother Pehr Johansson. Sara Sofia and Isak Pehrsson live in Stenstorp, an “udde” along the river Ume above Stensele village. They have three

children before packing up the whole “kit and kapoodle” and they move to Lönnberg. Their eldest and only son Johan (born 1851), all of five or six years old, has charge of his sisters Johanna Alexandra (b. 1854) and Sara Christina Sofia (b. 1856) for the move. Lönnberg is where my history remains today.

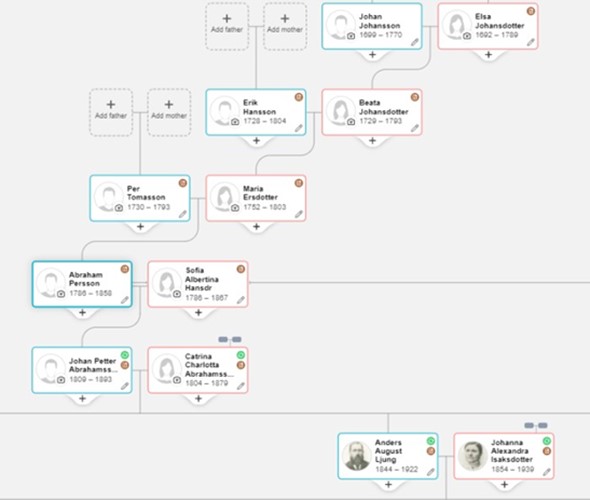

Figure 9: Ancestors of Lilly’s mother

Jacob Johansson or Jonsson (the records prove difficult to read sometimes impossible, destroyed by mildew) he lives in Ekkorsele, Degerfors kommun around 1725. His son Hans Jacobsson (b. 1734 or 1751) moves to Stensele in 1781 with his wife Elisabet Hansdotter also from Ekkorsele. They travel with their son, Jacob Hansson (b. 1778) which makes him only three years old for the journey. (This seems to eliminate the 1734 birthdate of his father also.) The family settles in Björkberg some 60 km distance southeast from Stensele. Jacob marries the widow Catharina Jonsdotter after she has nine children already with Jon Danielsson from Bastuträsk. Jacob buys a piece of land in the area of Skarvsjöby.

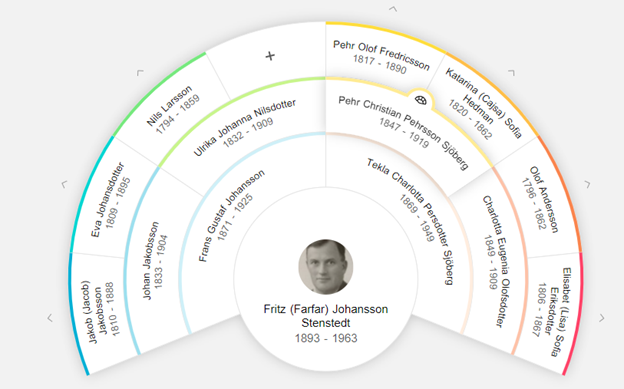

Catharina gives him seven children, obviously accepting her gift of fertility. Their youngest child Jacob (b. 1810) has no inheritance to land. But Jacob Jacobsson marries Eva Johansdotter (b. 1808) the youngest and favorite daughter of old Johan Andersson in yes Långvattnet. Later, I describe the circumstances of this land, but Jacob and Eva settle along the shores of the bountiful Skarven lake (Skarvsjöby). Their eldest son, Johan Jacobsson (b.1833), inherits this piece of land. Johan marries Ulrika Johanna Nilsdotter (b. 1832) a second- generation descendant of Jacob Hansson’s sister. They have seven children. The oldest and youngest deal with the family land, the two middle brothers try their luck in America, and the only living daughter marries a man in Arjeplug up north. The other two die while still children. The youngest is Frans-Gustaf (b. 1871) who marries Thekla Charlotta from Bastuträsk, and they have my grandfather farfar Fritz, born before wedlock.

Figure 10: Ancestors of Fritz’ father

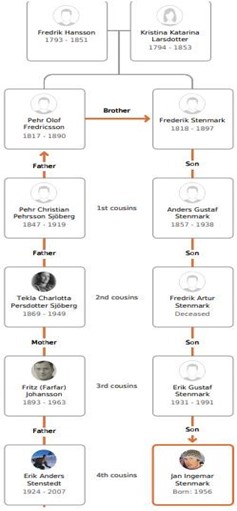

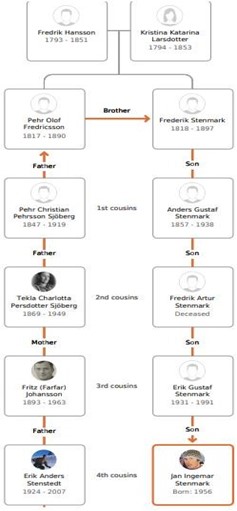

Frans and Thekla Charlotta marry shortly thereafter (1894). She descends from a fairly well- known Swedish family tree, named the same as the Stenmark family. Her father, Pehr Christian Sjöberg (b. 1817) lives in Bastuträsk. His father, Pehr Olof Frederiksson lives in Gubbträsk, where his father Frederik Hansson (b. 1793) originally moved the family. Before that, we have a Hans Olofsson to Olof Olofsson from Granön, born around 1700 and traced back to some Gulle

in 1400. Frederik Hansson’s oldest son, Pehr Olof inherits his father’s land, he leads to my family. His brother Frederik (b. 1817) moves to Umfors in Tärna. He intends to move all the way to Norway, but bad weather holds him to the Swedish side of the “fjälls” they say. Here, he takes the name Stenmark. His son Anders Gustaf Stenmark moves to Granön. The next generation Frederik Artur Stenmark moves into the main Tärna village, where his son Erik Gustaf sires Jan Ingemar Stenmark (b. 1956), who brings worldly fame to little Tärnaby, as the home of the renowned all-time greatest ski racer, Ingemar Stenmark, my distant cousin from Lappland.

Figure 11: Ingemar Stenmark’s 4th cousin relationship to my father Erik

From Umeå to Tärnaby is some three hundred kilometers along the Ume River. The 17th Century colonial farming expansion moves most of this 300km distance after King Charles, Karl XI orders a colonial study. These farming families must live simple, hard lives. The confluence of a constant battle against the climate and the growing family numbers, combine to force a territorial expansion throughout the area, and ultimately leading to my existence in America of course. When the wandering folks would find compatible soil here, with solar exposure and sufficient water, then they stayed, maybe. If they have ten kids, as seems normal, these youngsters must find their own corner of the forest along a lake or meadow, but often taxing authorities drive them deep into the isolated woods. Only one or two of the children can divide any of the developed property from the passing generations. The majority lose the advantage of previously broken land in the battle to produce enough during the short season to last throughout the long cold one. In these times, if a man fails to register for placement on a piece of land by the age of twenty-two, the Swedish military (serving the King) has rights to call him for national service. These centuries of European wars which precede the days of Swedish neutrality, find good use for the overflow of men from the North. Women seem scarce here, and social meeting opportunities are few and far between, as maybe the two major church weekends Easter and Mikaelehelgen prove. Thus, inter-family marriage occurs often.

Overall, the church dominates all other aspects of life here in the days of Lappland exploration. Food, shelter, and family, remain the highest priorities. But over this, religion transcends, the ancient Christian tradition claims responsibility for man’s fate, efter alt. The omnipotent power of God’s church demands obedience, of course, and regular attendance, as marked in the records, show that penalties can be stiff. For blasphemy or dissolution of faith, the burning stake of medieval days might often appear.

As we know, Renaissance humanism and Baroque style royalty regimes replace the medieval harshness all over Europe. Also, from its center in Stockholm, the united Swedish Lutheran church acts as Agent of the Agent of the Crown. In remote areas of wilderness, like the Ume River lands and Stensele-udde, change arrives slowly. But gradually, taxation agents of the Crown establish their prominence for the settlers, and eventually forest controllers (the Crown “KRON”) dominate the forest industry, stifling any private competition. As the church hierarchy passes regional control to more localized authorities, kommun power establishes its base. And finally, kommunal independence delegates the major community organizing power and communicates directly with the regional capital, and then on to Stockholm. For Stensele kommun, this means Lycksele, the big City in this region, controls the regional power (Capital) while Lappland “landskap” boundaries predominate. When they form Västerbottens ‘län’ (state), Umeå takes over the duties of capital city here for the State and the Royal Crown under a very socialist mindset.

Primarily, old records before the nineteenth century come from 1951 Mormon photocopies of church books. This archival method guarantees public access to most of the ancient religious census books, sustainably, and with room for unlimited study for the interested. Some

examples of the mobility shown by these new builders in Stensele “socken” come from lasting and well-organized taxation books, but also newspaper files as well. An excellent and helpful guide to these records is a book by Osian Egerbladh, Stensele 1741-1960 The Hundred oldest settlers, part X of a series by the same author titled “Ur Lappmarkens bebyggelsehistoria,” published in Umeå, 1972. From this book, I take most of the statistical information for this paper, mostly as to dates and place names. I looked up the microfiche myself in the Lycksele library and found the Hans Jacobsson confusion with birth dates, but the older the records the harder the writing style translates, and the less complete is the information as to place of birth etc. In Umeå, I found the Thomas Erik Norrman from Norsjö stuff and I finish this with his name without a birthdate or previous location.

Continuing with some examples of exchanges and local occurrences, I include some translations of Egerbladh’s books. For example, Hans Jacobsson from Ekkorsele in Degerfors buys one half of the first Luspen settlement in 1779. Erik Johansson and Matts Mattson from Lycksele settle first in Knaften, then Erik moves to Luspen in 1741. Hans Jacobsson brings his wife and young family. Hans Hansson who is either the son of Hans Mattson or the brother of Jacob Hansson, stays in Luspen which encompasses Storuman of today. Jacob Hansson moves on to Björkberg. The Hans Mattson from Uppenberg marries Sofia Olofsdotter from Ekkorsele, and their son Hans Hansson marries Sofia Johansdotter from Lycksele, and their daughter Sophia Hansdotter from Luspen marries Abraham Pehrsson in Ankarsund and the merry go round of family swap continues. More confusion has Elisabet Hansdotter from Hans Mattson, also Ekkorsele, who marries Hans Jacobsson and puts a Dahlrot after his name for distinction.

Hans Jacobsson Dahlrot and his wife Elisabet marry back in Degerfors. Their son Jacob Hansson (1778-1857) moves to Skarven while his parents stay in Björkberg their newly settled home, though the book also says that Hans Dahlrot dies in Luspen 1832. They move around lots clearly. There also appears many Hans Hansson’s Hanssons, and so on. This basic way of shifting name from father to son keeps it simple and confusing. Study the Stensele book for yourself. And inspect the family trees (ancestry.com) to get any sense from this paper. I conclude that Frans-Gustaf Johansson relates to the Anders August Johansson family from their connections in the progression. Some city Swedes say today that everyone in Norrland must relate to each other from one time or another. I felt that Stenmark must be related and was pleased to see the facts.

Jacob Hansson owns a piece of Skarven from 1818-1823. Johan Andersson buys it from an intermediary owner in 1828, and gives it to his daughter Eva, and son in law, Jacob in 1832. Frederik Hansson on Thekla’s and Fritz’s side, buys Gubbträsk property from Olof Pehrsson in 1821. When Frederik Hansson dies in 1851, this piece splits between the three oldest sons. Pehr Olof, the oldest, and an Anders August Frederiksson sell one share and they head for Norway, says the book. Of course, one of them winds up in Umfors, where he chooses the handle Stenmark to confirm that connection.

More in the way of this exchange stuff takes me back to Hans Hansson (born 1759). From Luspen, he moves to Långvattnet in 1789. He leaves this new place and returns to Luspholm shortly thereafter. Samuel Pehrsson from Bastuträsk, comes to Lycksele and takes over the newly broken Långvattnet farm around 1793. Samuel and wife Katarina Hermansdotter from Bastuträsk have ten children here. Katarina Charlotta Samuelsdotter (b. 1804) marries a Johan Petter Abrahamsson (1809-1893) from Ankarsund. His father Abraham Pehrsson (1796-1858)

leaves a long trail of new settlements. Abraham’s father also leaves a long trail of descendants, including, Pehr Thomasson (1730-1793) from the Norrman in Skellefteå and Maria Ersdotter (daughter to Erik Hansson in Stensund) have fourteen children, meaning Papa Pehr uses his virility into his sixties, I guess. Abraham is number nine, and how he meets his wife or where he starts his family, I can only wonder. But of course, Sophia Hansdotter lives in Luspholmen and they migrate all over the area. First, in Vällingby in 1819, then in Björkberg 1821, and they register in Slussfors, Rönnbäck and Ångesdal in 1824, Joby 1833, fjäll 1834, klippen 1841 and Vilasund or Umfors in 1844. Most of these sites are found in the Umnäs area on the Ume River towards Storuman.

If they marry in Luspholmen around 1807, this gives them several years to start their family with the help of the Hans Hansson family. Hans, of course, is the son of the original Luspen settler Hans Mattson from Ekkorsele. Then comes the oldest of the new generation Johan Petter who meets Katarina Samuelsdotter from Långvattnet and they settle in Nordanäs. In 1828, Johan buys half of Ankarsund from his father, then sells it in 1835 to move with his wife and young children upriver. Nordanäs lies one third of a Swedish mile (or 3.3 km.) north of Umnäs. It seems most likely that Abraham helps Johann establish his young family in such familiar territory.

The tax registers lose more credibility than church records from this old period. The safest facts include church attendance, reading ability, communion participation and of course marriage, birth, and death notices. Johann Petter and Katarina Charlotta have eight children, all baptized. The parents both read passably, they know the Lord’s prayer, the first catechism, and two books in the New Testament, so it says in the record. They attend church in Stensele once per year, which even by boat ride, back then, presents the family with a major expedition project, mostly for the men.

North of Stensele, the Ume River flows unaccompanied by a decent road. Not until 1920 does Storuman connect Slussfors with a summer road. Winter roads, however, provide the better communication for a wagon, but sixty kilometers seems a lot to sled or ski for a religious weekend. In the spring maybe, when the light makes time for travel and reasonable weather, Johann Petter probably makes his annual sojourn to Stensele to report on his family, take communion, and buy coffee, sugar, and tobacco if the year affords such luxuries.

Frederik Hansson from Stensele owns one quarter of Umnäs, one quarter of Gratön and half of the fjäll, which he sells to J.P. Abrahamsson, says the record. The whole parcel of three pieces of registered property sells for 335 Rdr. Rgs. (“Riks Dahlers RIKS, mynt”), in a transaction that occurs in 1838. No house exists on the lot, but one little hay storage cottage called a “fäbod” says the record. Samuel Pehrsson, the father-in-law must have helped J.P. with the deal, as the Stensele book claims that old Samuel should have ten rolls of tobacco from his “MAG” (son-in- law) each year. Sam moves back to Luspen where he dies in 1853 at ninety-one years of age.

Johan and Katarina maybe also row down to Luspen, each summer to visit dad, and keep him in tobacco, I guess. While thereby, they also visit the church, baptize another child, and report their taxes. I doubt if they can make this visit more than once per year, or if they can find

enough time away from their cows, but J.P. has “RÅD” (money) maybe, and a “piga” (nanny) and they were all tough, mobile, and hungry for church et al.

Their oldest son, cleverly named Abraham Petter Johansson (b. 1835), stays in Nordanäs with

his brother Johan Johansson (b. 1840). They inherit the right to buy their father’s farm, says the tradition. J.P. and his great quantity of land, reminds me of some Texas spread in America, but for the greater fishing potential here in Lappland, and the probability that most of the marshy meadow land resembles a swamp in best of times, and very little broken farmable land exists.

Not enough to support more than two families anyway I would guess. So, the other children see and seek their subsistence elsewhere. A daughter marries in Dikanäs, not too far away, another moves to Långvattnet, one son to Vilhemina for the army I guess, and two disappear to unknown destinations. This leaves our man Anders August Johansson (b. 1844) who marries into the Isac Pehrsson Lönnberg farm. First, he spends several years fishing above the Norwegian coastal city of Narvik. Nasty cold work this, but Anders August, “Ljungen” as they called him, proves his ability. He earns the lightning flash and flowery nickname, along with some spare money for the long journey home, and then, he moves south again to farming fortune.

At the edge of Stensele an “udde” sticks out into the Ume River, Stentorp. Here Johan Stenvall, the Stensele bellringer (“klockaren”) receives permission to build his family dwelling in 1824. In 1829, he sells half of his land to his son-in-law Pehr Johansson, who in 1838, buys the rest of the lot. And in 1852, Pehr permits his son Isak to build a home there. In 1843, Pehr owns one horse, two cows, and some sheep according to the tax inquest reported by our friend Egerbladh. Isak, the son, marries cousin Sara Sofia in 1852.

Following this, or shortly thereafter, for any number of unknown reasons, Isak, Sara Sofia and their three children pack up their little house and belongings and move the whole pile across the river and another eight kilometers upstream to Lönnberg. The round building-block formation of knot-logged houses of this time, permits their easy dismantling and reassembly, I guess. Isak moves the house in winter, starting small and simple, dragging a pile of logs with the horse, across the frozen river and up the snow-covered little path. In summer, the river couldn’t be crossed with a dry horse or wagon until about 1890, it says, when they built the first wooden bridge over the Ume. Johan Isaksson (b. 1851), the only son to Isak, works hard at only eight years of age with his father to build a brand-new farm on a stony hill without much previous sign of life support potential. The name of the hill comes from Pehr Christian Rad’s wife Great Stina Lönnberg (b. 1807). He was the first “kyrkoherde” (head pastor) in the Stensele church, records say. Stina receives Lönnberg property as “änkeställe” (widow’s place) after Pehr dies. Her daughter marries some Crown’s minister from Uppsala. They leave the Lönnberg farm to a son, Karl Pehrsson. With money from the sales of his Stentorp place, Isak buys a piece of this rock (sten). He probably digs for well water, though a stream runs nearby. He also taps any other local resources available on this rocky hill above the swampy glacial land in Stensele.

The forests grow thicker during the nineteenth century, and this changes the entire look of Lappland’s countryside. Also, it provides an economic opportunity in logging and paper, which brings on civilization from the South and West from Europe, and the money even comes to lonely Stensele and Lönnberg. From 1850, this tide must wait for fifty to a hundred years, and time for the forests to double in size. Isak and Sofia live through much of this time as farmers, for their cows and sheep provide milk and wool. The horse and a burgeoning crop of family in Stensele socken, take their turn, feeding domestic animal producers. They also have hens.

They grow potatoes and barley to mill for flour. The potatoes, they can even mix with anything: bread, pancakes, dairy food, and meat. The barley stalks and husks add food for the animals, and Stensele has a water mill at this time, for flour. They sell cheese, butter, and leather as trade items in Lycksele for a bit of wheat flour or sugar or other luxury extras, representing a small piece of the common life changing and evolution coming for most farmers in the area.

During this early era, transportation presents a great problem. Boats in the summer combine with lots of walking, cutting, and marking trails. They carry all their goods on their backs.

Winter, of course, means homemade skis, sleds and horse drawn wagons. And Church, usually far away, attracts with supreme import, authority, and devotion. Taxation, of course, works through this channel also. In calling for army duty, the Crown or state feeds its ranks, using major church holidays, and information from the church records.

All social life then, also revolves around four major church celebrations. Midsummer is number one, which interrupts the summer rush of work and thus, attracts the smallest numbers.

Attendance at Mikaelhelg, number two, receives the greatest number of youngsters, often finding a new place as “piga” for girls and “dräng” for boys. This also applies for winter help, indoors utilizing “getare” and junior farm hands, dräng, are used for the summer and winter, because all hands help, and they hunker down as a community family. Christmas, number three on the list of major church holidays, means the most, and celebrates usually at home. At Christmas, the family shares its blessings in preparation for (or as part of) the awesome winter. Number four Easter, celebrates spring, the loveliest time of all in Lappland, sun and snow, daytime and nighttime, a respite from work, and the promise of summer’s blessings and hope for a food bearing harvest.

The Pehrson family survive with their small needs and minimal production. Somewhere however, the parents grow very weak through the 1860’s. Sara Sofia dies in 1871. Isak loses sight one year later. Johanna marries Anders August Ljung also in 1872. She takes care of her new husband, brother Johan, sister Sara, and papa Isak who takes another wife. The burden shifts from the old family to her new family as the older generation looks after itself and her “syskon” marry away. Johan marries Anna Maria Olofsdotter from Åskjelle in 1876. Sister Sara stays on to look after Isak and his new, old wife. This still leaves three families with children living in Lönnberg: two in the small house and the Pehrson’s big house and only a few acres of areable land for all. Isak and Johan built the big house which stands today (1983) in 1860.

Johan moves to the little shack they brought from Stentorp. Tough years lie ahead, according to the records. Little Johanna gives birth to her first son Johan August Ljung (b. 1874). Pehr Alfred, the second in line, born 1877, attracts a case of new world fever as a teenager, after the first brutal years of his life to begin a family of emigrants to the new world. Two serious winters follow in a row. Hunger, famine, sickness, and death sweep the Lappland area.

I found a clipping from a 1935 newspaper where an eighty-year-old man describes the hard times. He tells of the year 1877 when the snow from a severely cold winter lay one meter thick on midsummer’s day. They barely have time to lay some potatoes when the ground refreezes in the early fall. Both the barley crop and the potatoes perished, it says. All summer, as long as it lasts, the family prepares for the rough winter ahead. They manage to get some wheat, which they mix up with ground birch bark to make bread. The trick here, demands something to grind the bark fine enough for the body to possibly digest. The nutritional value might seem negligent, but the filling quantity, might satisfy unbearable hunger, I guess. With nothing else to eat, they manage to force the foul-tasting bread down. Also, it says they grind up moss and some leaves with dried berries, which they boil to make a mush or “Väll.” They have no salt, so the fish they catch in summer only sour when they try to save them for the hardest months ahead. They eat all that they save or find, and they barely survive. He continues in the clipping with the winter when the whole family becomes sick. Three sisters die, he and his brother lie unconscious for six weeks. Some woman comes in to feed the animals. She discovers the family one day, just visiting her neighbors, they all lie on the floor and all the sisters lie there dead. She brings more help and puts them all to bed. This neighbor saves their lives, she feeds the animals what little they have, she can give water to the sick, and spare some food from her own farm maybe. Finally, the father recovers enough strength to move about the farm and they survive, four out of seven. One can only marvel at the persistent faith in God and the care of neighbors under such circumstances. The clipping goes on to say that no word of complaint ever breaks the silence. Then, they criticize the young people of 1935, who don’t know hard times. I wonder at this last part since Sweden at the time, faces as serious an economic crisis as the U.S. depression.

Johanna Ljung knows stories from her own family during these hard winters, says Irene. She tells her children some of the horrifying tales but holds the memory to her grave. No one can talk about these years in Lönnberg, very few stories carry on through the new generations.

Oldsters may know the awful taste of bark bread, but it sounds unrealistic even to this 1930’s depressed generation. Food still means survival, even today, weather provides a blessing or a curse. So, they put the responsibility on God to save them or let these explorers perish. Even my father’s morbror Alfred remembers from his San Francisco perch, the foul taste of stinking fish, meager potatoes, and rotten fruit. They relate sternly to our choosey appetites today.

In Lönnberg, they survive this harsh winter of 1877 without great catastrophe. In Skarven, less than eight kilometers away, they feel nothing like this problem, it seems. The farms sheltered behind the cover of the Skarven hills freeze hardly ever. Also, they have the advantage of a long-established family farm and possibly saved some money to buy salt, at least. The fishing always saves places like this and Långvattnet provides a unique type of wealth in fine wilderness fashion. All around, however, isolated families starve and die in famished sickness. As seen, neighbors go out of their way to check with each other and help when possible. They seem to build a strong community when they follow the moral principles of Christian charity. Because of these large families and their growing need for farming space, many move deeper into the woods, far away from the nearest neighbors. Without money to buy land, they simply settle by a small stream in an out of the way corner of nothingness. The cow dies, no potatoes, papa lies sick, and they can only pray to God for mercy.

The natural growth of the forest barely supports the wild animals over the summer. Then, winter freezes a deadly hush into nature, when lakes everywhere provide endurance for fish, but to fish, demands equipment and energy, especially in mid-winter. A family can survive on stored fruits (mostly berries) and potatoes (maybe some carrots?). But meat, milk, and bread supplementing the others, provide real health and sustainable power to prosper. Here, hunger drives the weak away and forces the best from the strong to get yield from this harsh climate. It forces the serious to fight harder, one could say. But some flee as far as America, where they can meet up with the same conditions. But usually, so the story goes, America creates a paradise for the lucky. Like the fortunate who find a sturdy settlement along the Skarven.

The hills, meadows, and lakes of Skarvsjöby seems a bit of paradise for these early times. Many families can live off this prosperous community, and they mark their place in Stensele history. The farm in question obtains stable continuation from the time of Jacob Jacobsson and Eva Johansdotter in the late 19th century. One quick note from the records first, on her father and mother when they move to Långvattnet, around 1790. Johan and Maria Katarina leave Hjuken, Degerfors the home of her parents right near Johan’s family the Anders Andersson of Mjödvattnet, Burträsk. Johan leaves a huge family of fifteen excluding himself, Maria has five sisters. They take to the river roads towards Stensele, it says, with three young children. Mama carries the youngest and the other two manage to walk beside the cow. First, they plan to settle along the Näsvattnet, but then it appears someone already has taken the choice spot. At Långvattnet, they live under a tree for the summer, then Johan manages to raise some kind of shelter for his family and the cow. They prosper along this lengthy lake shore beside a decent cliff. Only two of their sons stay in Långvattnet, the rest establish families nearby, including Pehr Johansson in Stentorp and Anna Christina in Luspholmen who create the parents of Johanna Alexandra Ljung. The youngest daughter Eva brings me back to Skarven and the Jacob Hansson line.

Hans Jacobsson and Elisabet Hansdotter Dahlrot come to Storuman in 1781, they move on to Björkberg and eventually back to Luspen, where Hans dies in 1832. They have at least three children along the way. Frederik Hansson lives in Bastuträsk. He gives his brother the piece of Skarven land in question in 1818. This brother, Jacob Hansson from Björkberg, marries Katarina Jonsdotter (1767-1861) the widow of Jon Danielsson (1752-1800) from Umeå. The marriage happens early in this first decade of the new century. Jacob Hansson inherits the responsibility for Jon’s children. These nine given, Jacob and Katarina have seven more of their own, making the largest family yet seen in Stensele. The oldest son Daniel Jonsson inherits Jacob’s land in 1821, I think, he merely buys a piece of this land, cheap – fifty riksdahlers. Daniel lets brother Carl Jonsson take over the land since he himself likes Bastuträsk. In 1823, Carl receives permission from the land council in Lycksele to divide the property. He sells half of this to his half-brother Hans Jacobsson (b. 1804) the oldest son of Jacob and Katarina, again savoring a good deal. Johan Andersson, our friend in Långvattnet, buys the other half for Eva his beloved baby daughter. Jacob Hansson still holds his piece here in Skarvsjöby. He must help his oldest son with a loan, for Hans Jacobsson takes care of his father for life under obligation of the standard contract of the time, where parents deal generously with their children only for due receipt in return to avoid neglect in old age. This precedes any state pension program.

The records say Jacob and Eva must keep old Johan supplied with his favorite cheese and a new pair of woolies each year. Usually, the children own a tenth of the property so the parents can recall their share any time everyone is alive. This also prevents early sale and avoids any abandonment of the oldsters. But we know, youth has a mind of its own and flees freely, even in Victorian Skarven.

Jacob Jacobsson settles seriously into the Skarven community, while Johan Jacobsson (1833- 1904), his oldest son, inherits the land given to Eva. One of his brothers Jacob Jacobsson (1836- 1896) marries a sister to Sara Sofia Isaksdotter from Luspholmen. This line also stays in Skarvsjöby, Johan Jacob Jacobsson (1856-?) adds another generation to this name game. Another brother Abraham Petter Jacobsson (b. 1836) marries a Stensele girl of no relation and has nine children to add to this blooming lake community, as I learned.

Figure 12: Skarvsjöby and Stensele

Skarvsjöby lies twenty kilometers south of Stensele. Away from the Ume River, a small stream leaves the lake and runs down the Skarven hill and into the big stream “Storbäcken” which connects ten plus winding kilometers later with the Ume across from Stensele church. The hill provides dry soil, good drainage, grassy meadows and as easily reemphasized, milder winters. The water means fish and game all the year round. Also, there’s swimming (bathing I should say), boating, skiing, and snowmobile paradise over the frozen pond. Woe.

Johan Jacobsson marries Ulrika Johanna Nilsdotter a granddaughter of Hans Jacobsson Dahlrot, from Björkberg. Her mother, Ulrika Louisa Hansdotter, adds a sister to the Jacob and Frederik Hanssons’ line. In this line, Ulrika Johanna marries her cousin’s son. In order to skip this generation, I note that Jacob Hansson (b. 1778) is seventeen years older than his sister Ulrika Louisa (1795-1872). Unfortunately, no clear account of the Hans Jacobsson (1751-1832) family exists, to my findings anyway. The names seem so very common, and get confusing with other Hans Hansson’s Hanssons etc. They float through the old church records, and I found one Hans Jacobsson family with a Jacob and a Hans for sons, but the birthdates didn’t match. This family from and around Stensele on the Ume River moves frequently and leaves only a faint trace of their exchanges and fainter signs of their relations and background.

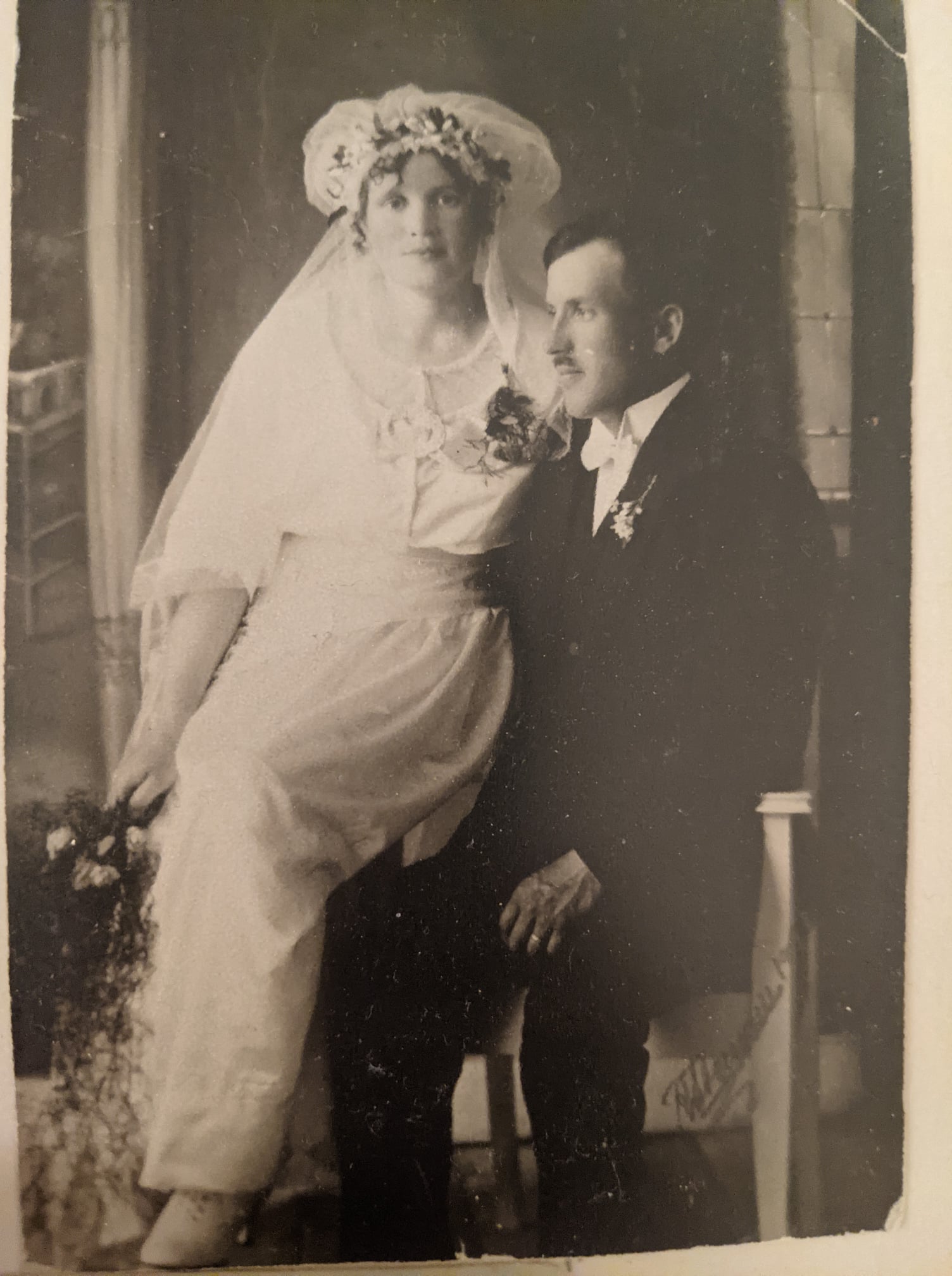

IV. Farfar’s parents – Thekla Charlotta and Frans Gustaf

This brings me to the birth of Frans Gustaf Johansson born 1871 in Skarvsjöby, the youngest of Johan and Ulrika’s children. Thekla Charlotta comes into the picture from Bastuträsk, a small village downstream from Stensele, now joined with the town of Gunnarn. A picture of her parents hangs on the wall in Skarvsjöby today alongside an even older picture of the brother to the forefather of the famous Ingemar Stenmark, Pehr Olof Frederiksson (b. 1817). Pehr Olof sports a long beard in the picture, and his wife has a heavy looking gray suit. Pehr Christian Sjöberg (b. 1847), the son, contrasts with his father, sporting short slick hair and a darker suit. The styles change even then, as the portrait pictures show. In this picture, they all four look extremely stern, and unaccustomed to the camera. What can they think of the world, which now looks back on their leavings and doings? Even in black and white, the eyes show similar family resemblances, maybe.

Figure 13: Tekla Charlotta’s parents and grandparents

Frans Gustaf Johansson (1871-1925) inherits half of father’s land. His oldest brother Johan Johansson (b. 1857) starts his own clan also along this resourceful Skarven lake. A brother and a sister die in childhood. The other two brothers move to America. Suddenly, this place name appears as destination and demarcation. Instead of a military career or the basic continuation of tradition, the boys also seek new work elsewhere, but with Skarven roots. Industry and revolution capture the history of Europe. The modern world takes its new shape. And science even comes to Lappland.

Two buildings still stand in use on the farm in Skarvsjöby today in 1983. They speak much of the environment, and the local history. With very few tools and only his sons to help with the labor, Jacob Hansson builds the first place before the nineteenth century. This brings up transportation problems since the lakeshore provides only ground, rocks, trees, and access to water, everything else they must bring in on their backs or drag behind a cow. To start building a house while the summer lasts and so much work in breaking the ground for a first crop, the temporary shelter makes for a cold first winter. Maybe a slightly bigger place the second year, like a fäbod but tight and with a crude oven or smokey stove. This means some crowded times for a young family, and probably, as is tradition, the animals sleep inside the warm house in winter, so as not to freeze. Any metal or glass, all the iron tools and cooking gear that cannot be made from stone or wood, comes from Stensele, and there, from the markets in Lycksele.

Somehow, Jacob manages to raise a substantial structure on his land near the water. He has a forge, for the hinges, which still today look homemade. The construction process seems interesting.

Jacob Jacobsson winds up with the house and therefore, maybe he builds it himself, meaning construction date is probably after 1832. It seems the whole building comes from the same time, but maybe Jacob Hansson or someone else even laid the foundation and the living half dates back to 1790. Regardless of who, or when, they play with stones already there, and move others into even flat rows with supplements of dirt and moss, using movable rocks to landscape. This operation takes practice and care to avoid shifting dirt from spring run-off.

They succeed, and the house lasts nearly two centuries. Even horizontal lines can change with the timber they place at each level. Esthetically, they use even logs, and this precision shows all the way up, with a few wedge additions to compensate for different sized boards (hewn logs). Flat stones and evenly shaped logs hold a strong wall and thereby the shelter holds a strong roof. The axe hewn logs shine even without precise edging but beveling and notching with the axe make for a tight fit. Wood plugs and moss insulation blend into the beefy lumber. They treat the final product with sap for protection, in the old days. Today, the Swedish red paint blends the old timber with the new to color the landscape of red farmhouses. They use massive logs which run the length of the walls for the roof. These hang on a beveled notch to fit at each end, then they hang smaller shoulder tresses along this length which hold the first layer of thinner roof planks. In these old days, a layer of “NÄVER” (birch bark) covers and then mixes with other handmade shingles for a tight and insulated roof.

Of course, they make everything possible with the available tools right there, on the spot. But the windows come from town, so they find special place for these luxuries. The doors take days of layering, using the finest thinnest boards they can cut. They pattern the doors to match the window or shutters. Later, they might install a lock from town. The hinges are a simple design with a hook on the doorjamb, and a folded piece attached to the door which hangs quite effectively. Jacob’s forge also makes some iron nails to reinforce in places, like the hinges. Also, with the forge they make handles, horseshoes, and plows or spades. Imagine the work to cut and sharpen these tools with a stone. Imagine the time for two or three men to build this house, a monument for its day, in the short season of summer. Massive timbers for strength and winter tightness by being creative, suffice for the exterior décor, but inside they have time during the long winter months to smooth out the walls and tighten the roof. They learn to build furniture, of course, and eating bowls, as well as barrels for water, a loom to make their own clothes and maybe even picture frames, and carvings for the talented.

The oven might include homemade bricks, a type of cement and some pieces of metal for fire protection and cooking. The kitchen takes half of the house, with sleeping places along the walls and a large table for eating. The fire in the stove is the center, for food and heat. The other half of this house is the barn. During the coldest months of the winter the animals were well acquainted to sleeping with the family, or the other way around. This seems most possible in a smaller fäbod type arrangement, where the animals might have their own fäbod, without heat, forcing them into the family shack in the coldest times. (Food producers need and deserve shelter from this climate, of course.) To picture three generations of humans, ten people or more, sleeping along the walls, with a cow and the sheep sleeping in the middle of the floor while some hens might take to the loft with the cat, this stretches the imagination. I like the idea of lofts for sleeping in the smoky warmth, while the cows and the swine can have the floor. Jacob’s place in Skarven innovates with ventilation I suppose and hope, of course. Mama and Papa deserve their own room, and the animals have the whole other half of the house – this is a castle. They shuttle the heat easily through holes in the top of the wall, and they could use a little fan for help. Eventually, the family builds another small house alongside, for the older generation, and then another big house for the Frans Gustaf family. For progress. Progress progresses, I guess. In Skarvsjöby, progress may lack prosperity, and loses on the scale of modernity, but the family grows strong with the community.

It takes another century for the home craft industry and independence from town to fully disappear. Roads, money, and civilization invade with all the lure of modern industrialized comforts, and all the problems, but community takes over. Large families, poor soil, and harsh climate, however, drive so many away from Lappland. First, the boys move to the city for army duty, obligatory for every twenty-year-old since 1890. Before this, they call them in if they have not settled themselves on a farm by age twenty.

From the cities, they find that unemployment comes when factories, and wealthy entitled nobles, play their power games to keep labor prices low. Then, they dream of moving to America, where they say the industrialist capitalist always needs bodies, and farmers might even chance striking gold. Once a family sends one son abroad and hears of the successful ventures in an easier climate, with plentiful work, frontiers opening and money potentially for all, with so many things to buy, the fever spreads fast. The transition to machinery and to the city coincides with the movement to America, then the modern system of ever-growing economies, and the acceleration takes over. I can’t help but look back on the history, and older ways of the home-crafts economy, and see something lost to our rushing, rootless and accelerated souls. Satisfaction without physical labor it seems, makes for a different sense of pain, life, and God, maybe.

Some hundred years after the foundation of the first house, Johan Jacobsson and his sons build another house right next to the first one in Skarvsjöby. The oldest son here, Johan Johansson (b. 1856) takes his half of the inherited land value somewhere else. The youngest son, Frans Gustaf (1871-1925), takes both houses and a smaller amount of land. Before Thekla Charlotta arrives to take charge of the new generation, the two other brothers set out for America. I assume they, in turn reject a paternal offer to stay, but they decide instead on venturing forward with the adventurous journey for new parts, across the world. Nils Reinhold (b. 1858) moves to Stockholm sometimes instead of military service. Then he follows brother Carl Aron (b. 1868) to Minnesota. This leaves Frans G. with freedom of space to build a family in the new house. Johan and Ulrika live in the old place into the twentieth century.

Figure 14: the church in Stensele

Thekla Charlotta Sjöberg comes to church in Stensele, as far from her Bastuträsk as Skarvsjöby is to Stensele. In the region, 1885 dates the finish of the kommunal project to construct the massive Stensele church. The standard chapel design makes room for all two thousand distant members of the congregation, with a second level for benches, halfway up the ten-meter walls. The steeple reaches over thirty-five meters in Stensele – the tallest and largest wooden church in the whole country of Sweden, north of Gävle. This means pronouncing a communal hub, as the mighty bell-tower calls to the distanced, growing, and pious congregation. Each family donates twenty man-hours labor plus all the timber they can afford to build this communal project. They use a new hydro- water powered saw for the smooth wall finish boards. The main posts measure over sixty centimeters width. Still today, the Stensele church ranks second only to the Margareta church in Lycksele for authority in southern Lappland. But for its size and its universal congregational support in these old days, the Stensele church still stands tallest over the Ume River area.

Thekla Charlotta Sjöberg and Frans Gustaf Johansson meet at one of these festive and holy, church inaugural weekends. She moves to Skarvsjöby as paid help or “piga” since sister Eva moved to Arjeplug. And the Jacobssons might need some “getare” help with their cows. This ancient culture accepts the young courtship, and even the practice of the suitor climbing into the chosen window to sleep together amorously. But, the one convention, which holds strong, says the boy must sleep on top of the bed covers. Frans, however, breaks this rule somehow, and crawls alongside his mate. Therefore, my FarFar Fritz enters this world without the sanctity of Christian wedlock, and according to the church and its code, which also controls state and Crown law, Fritz cannot inherit the “fastighet” (parental estate). Regardless, Frans and Thekla marry in time for their next son Robert (b. 1895) – legitimate by law. They continue and raise a typically huge family (lots of boys). The times remain difficult, however, with heavy winters recorded before the turn of the century. One old neighbour remembers Thekla Charlotta as the type who takes in small, hungry children on their way to school or work, for some milk and bread. Again, these children can live in the comfort of the well-established family on its farm, and the luxury of many cows, where food exists, and Thekla C. generously extends her small gift for the community.

The resourceful Skarven farm raises another huge family. First, three boys before the new century: Fritz (1893), Robert (1895), Aron (1898); and Gustaf (1903), Knut (1906), Sören (1907- 20), and Tora (1909-09) the only girl dies at six months, and Teodor (1911-65). One must assign a “piga” to help Thekla with this heap, because it seems physically impossible for one mother to attend cows and so many children single handedly. Ulrika Johanna, grandma, helps as long as she’s able, until she dies in 1909. After this, the older boys probably work with their mother in the dairy, as well as alongside their father in the field. Knut born in 1906 still lives along the Skarven in 1983 and tells me they never had a “piga.”

Maybe he doesn’t know or remember.

He does remember the amount of work assigned to his mother because men should not work in the kitchen or in the dairy. In reality, the woman works just as hard as the man, if not harder, in this culture. But each sex has their traditional duties with a clear dividing line in between. Man tends to construction and agriculture; he cuts and splits wood for the winter. He cares and feeds the horse. Woman cleans the house, fixes all the food, washes all the dishes and the clothes. She also has charge of feeding and